September 30 2025 at 06:16AM

Beyond the Blueprint: Why Successful Adaptability is Not a Technical Feature, But a Project Delivery Outcome

As project stakeholders who deal with the various construction industries, we must be ready to face the pressure of sustainability demand and responsive to rapid urban changes.

Adaptable buildings, particularly those using modular construction, are increasingly presented as a key solution, assets designed for more than one lifecycle, capable of being reconfigured, expanded, or relocated to meet future needs.

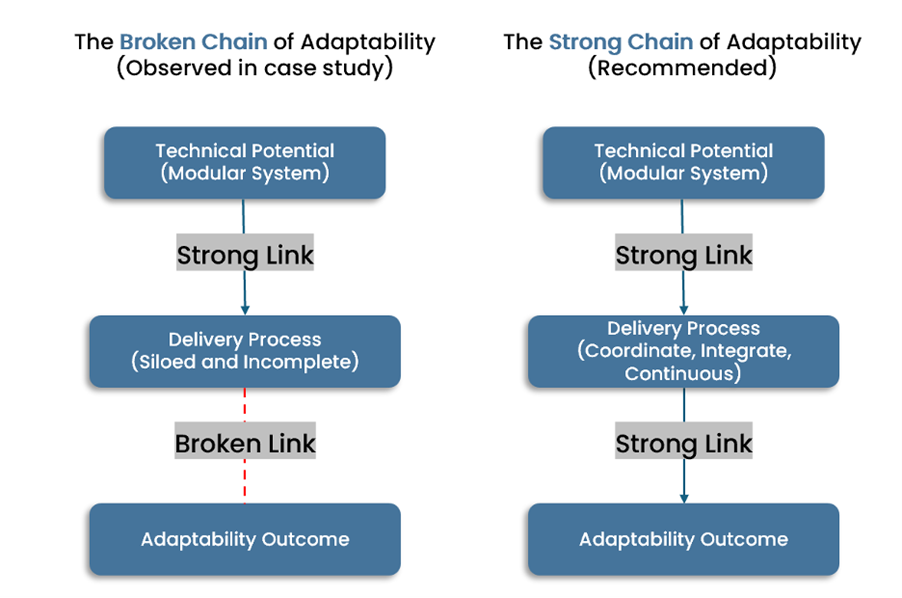

The promise is promising, which is less waste, longer lifespans, and greater long-term value. However, the reality on the ground often falls short. My recent Master’s research at TU Delft, which analyzed two distinct Dutch modular projects, revealed a crucial insight: successful adaptability is not a technical feature, but an output of a holistic project delivery system. There are gaps in the project delivery system, which creates a "broken chain" where advanced technical design is hindered by a fragmented delivery process, which leading to disappointing results.

The Adaptability Blind Spot

The core of the problem lies in the mismatch of a socio-technical. We have the technology to create adaptable structures, but our project delivery methods are often still linear and siloed, or even too focused on short-term metric completion (such as cost, time, and quality).

The two case studies in my research were a perfect illustration of this disconnect. One project, an office expansion, benefited from an informal, trust-based relationship between the client and contractor. However, this lack of formal structure meant critical long-term goals were missed. An ambition for vertical expansion was impossible due to an inadequate foundation, and a lack of lifecycle documentation made future reuse challenging.

The second project, a relocatable housing development, utilized a highly efficient, contractor-led Design & Build model. The superstructure was masterfully designed for disassembly. Yet, it was built on a permanent foundation, which creates a fundamental contradiction: a reusable building that the foundation couldn't be moved.

In both cases, the technology was sound. The failure was in the delivery system.

Three Keys to Building a Strong Chain of Adaptability

To bridge the gap between ambition and reality, project managers must shift their focus from solely delivering a technical product to architecting an integrated delivery system. My research identified three critical realignments to achieve this:

- Realign the Process: From Linear to Iterative

Traditional, sequential workflows are a primary cause of coordination breakdowns. To hinder this, we must restructure the flow of activities to be more proactive and iterative.

- Front-load Lifecycle Decisions: Critical tasks like Design for Disassembly (DfD) planning should not be afterthoughts. They must be embedded in the earliest design phases to influence layout, structural design, and even procurement.

- Embed Feedback Loops: Create formal mechanisms for construction and post-occupancy insights to flow back to the design team. An iterative process allows for refinement.

- Realign the People: From Ambiguous to Accountable

Critical tasks often fail because they lack a designated owner. Adaptability requires explicit, contractual responsibilities across the entire project lifecycle.

- Use a Refined RACI Matrix: Go beyond defining who is Responsible for a task. Clearly establish who is ultimately Accountable for long-term deliverables, such as the final handover of a material passport or a disassembly guide.

- Ensure Early and Continuous Integration: Specialists like MEP and structural engineers must be involved before technical freezes, not after. A hybrid coordination model that combines the formal accountability of contracts with the collaborative communication of early-stage workshops is essential.

- Realign the Plan: From an Open End to a Continuous Lifecycle

A project’s lifecycle doesn't end at handover. For an adaptable building, this is merely the end of its first life. The project plan must create a formal bridge to its second life.

- Mandate Lifecycle Deliverables: The handover package must include more than just the keys. It needs comprehensive documentation (as-built drawings, material passports, and disassembly protocols) that makes future adaptation feasible.

- Assign Post-Use Ownership: The plan must answer the question: "Who is responsible for the building's adaptability after handover?" This role must be clearly assigned, whether to the client, a facility manager, or a circular consultant.

The Takeaway for Project Managers

The promise of adaptable buildings can only be realized if we, as project managers, expand our role. We are not just executors of a predefined plan. We are the architects of the delivery system itself. By intentionally aligning the process, the people, and the plan, we can forge an unbroken chain from technical possibility to real-world value. By doing so, we ensure that the promise of adaptability is not just designed in theory but successfully delivered in reality.

About the Author

Fransiskus Xaverius Prisyafada is a construction professional with an MSc in Construction Management & Engineering from TU Delft. His work focuses on improving project delivery strategies for sustainable and adaptable buildings. He is currently seeking new professional challenges and is open to connecting on LinkedIn.